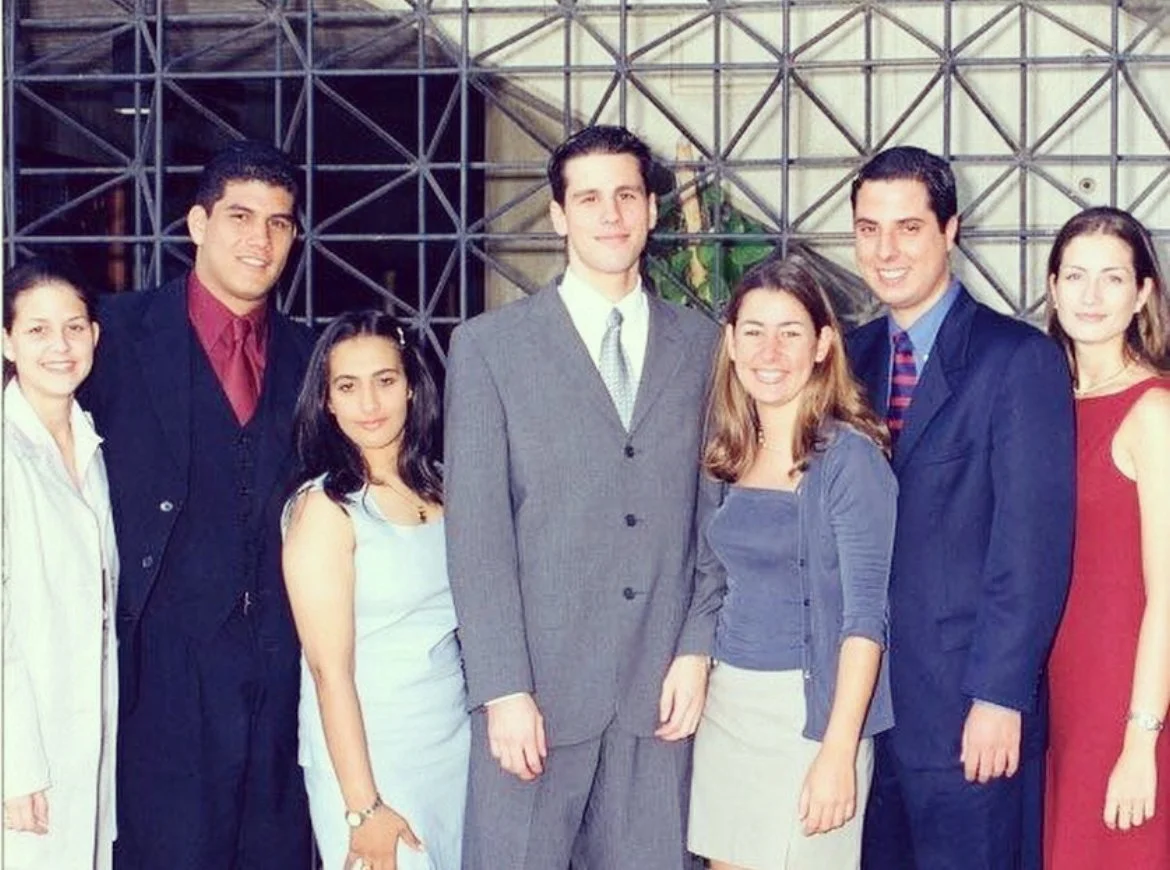

Here I am on January 21, 2017, the first day of Trump’s first presidency, at the Women’s March on Washington.

I'm an immigrant (twice an immigrant, in fact) with a multicultural background. I’m also a middle-aged, married gay man and a feminist art historian. For these and other reasons, I've consistently voted center-left throughout my adult life. I’ve voted for Barack Obama, Hillary Clinton, Joe Biden, Kamala Harris, and other leftwing candidates at every level of government. Most importantly, I’ve voted against Donald Trump three times. And in Venezuela, I most recently voted for Tamara Adrian, the first trans woman legislator in the country, during the opposition primaries ahead of the 2024 presidential elections.

My voting history reflects a set of principles I believe in: gender and racial equality, LGBTQ+ rights, women’s right to bodily autonomy, respect for the dignity of immigrants and incarcerated people, freedom of speech, and the separation of church and state. These same principles underpin my absolute opposition to the chavista regime in Venezuela — a militarized authoritarian system responsible for widespread extrajudicial killings, tens of thousands of political prisoners, and the mass exodus of nearly nine million Venezuelans over the past decade.

I deeply reject Trump’s authoritarian turn in the United States, just as I celebrate the fall of Nicolás Maduro in Venezuela. I dare to hope that democracy might finally return to my country of birth, even as I worry about the global implications of the budding revival of the Monroe Doctrine.

This is not a contradiction. It’s simply me, one person, trying to hold on to a set of values in a world that’s not as neat as a theory text dissected in a seminar room or a curator’s label framing an artwork on a gallery wall. Life is messy. Brutally messy.